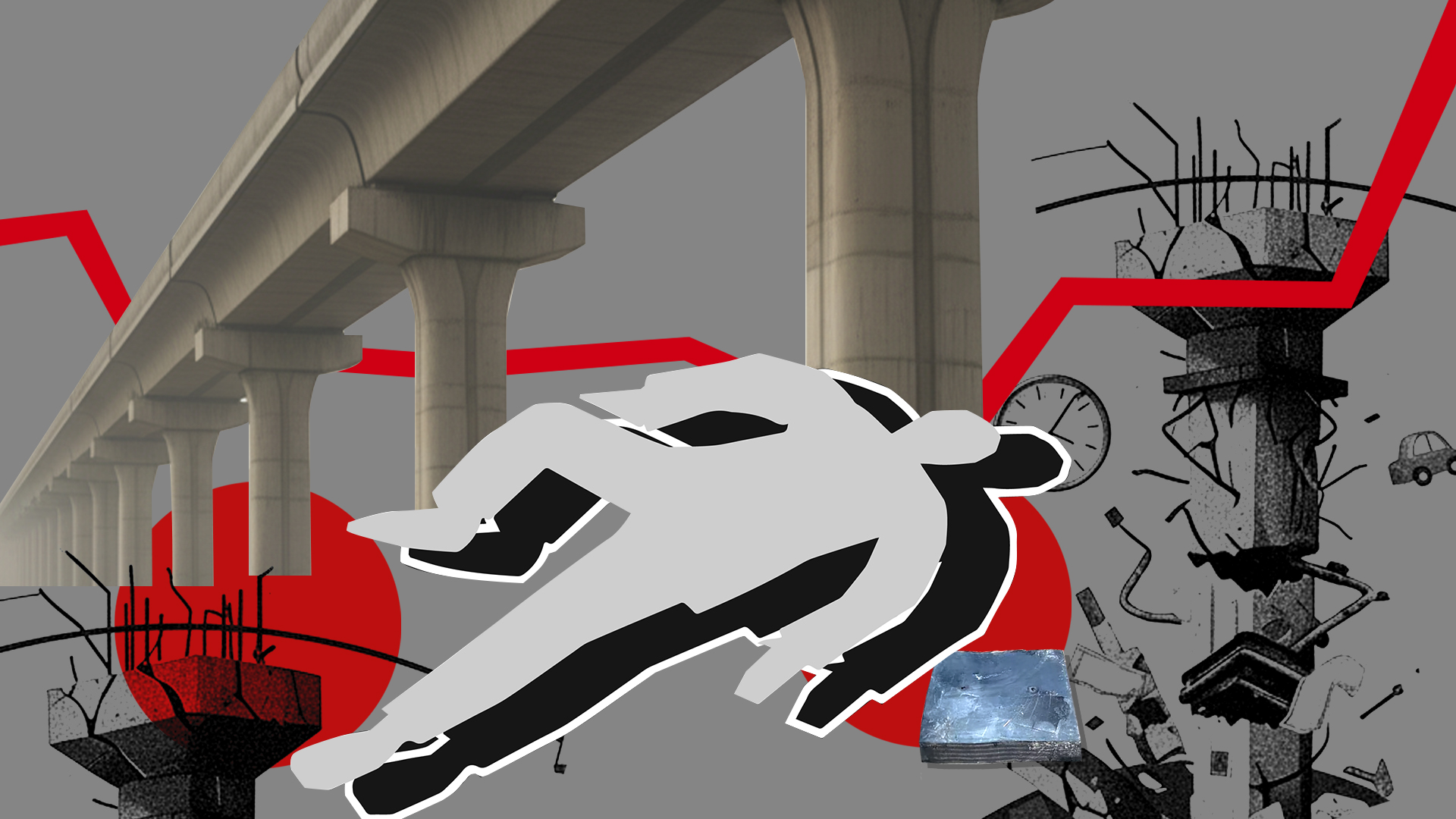

Farmgate tragedy and the question of state liability

Last month, a pedestrian tragically lost his life in Farmgate when a bearing pad fell from a metro rail pillar. Two other people were also injured in the incident. Following the incident, Road Transport and Bridges Adviser Muhammad Fouzul Kabir Khan stated that the family of the deceased would receive Tk 5 lakh as compensation and that an eligible member of the family would be offered a job at Dhaka Mass Transit Company Limited (DMTCL). A five-member committee was also formed to investigate the incident.

In the absence of a provision for compensation for accident victims under the Metro Rail Rules, 2016, prompt response from the government is commendable, especially when the government cannot ignore its responsibility in this tragic incident. Besides, the amount offered is inadequate considering the severity of the loss. It should be noted that the amount—Tk 5 lakh—was not just meant for the financial support of the family. Rather, it was stated as compensation for the loss. According to the Law Dictionary, "compensation means indemnification or payment of damages, which is necessary to restore an injured party to his former position… money which a court orders to be paid, by a person whose acts or omissions have caused loss or injury to another, in order that thereby the person damnified may receive equal value for his loss, or be made whole in respect of his injury." Now the question arises: how did the government determine the actual extent of the damage suffered by the victim's family? Shouldn't it be the court deciding the amount of compensation to be awarded?

For instance, in compliance with a High Court order, Bangladesh Fire Service and Civil Defence and Bangladesh Railway jointly paid Tk 20 lakh as compensation to the family of Jihad, who died after falling into an abandoned deep tube well in Dhaka's Shahjahanpur area on December 26, 2014. In both incidents, there was evident negligence on the part of government authorities, making the current compensation seem disproportionately low.

In the event of a fatal accident, the family members of the deceased may seek compensation under Section 1 of the Fatal Accidents Act, 1855. However, in practice, initiating legal proceedings against a government body often proves to be difficult or impracticable. Consequently, the only viable means of obtaining compensation is by filing a writ petition under Article 102 of the constitution. It is important to note, however, that filing a writ petition is not the conventional method for claiming compensation. According to Article 102, when no efficacious alternative remedy is available, an aggrieved person may invoke the writ jurisdiction of the High Court Division. The legislative intent behind this provision is to ensure that individuals are not left without recourse when no other legal remedy exists. Therefore, a specific legal remedy is required in situations where loss has occurred as a result of negligence on the part of the government. However, apart from compensatory measures, what is truly essential is a thorough and transparent investigation to ensure that those responsible for this act of negligence are held accountable.

From a legal perspective, the state bears responsibility under the principle of strict liability. This doctrine holds that the government can be held accountable for harm caused by its actions or those of its employees, even in the absence of direct negligence or wrongful intent. A key feature of strict liability is that a person or authority cannot evade responsibility by assigning dangerous tasks to independent contractors. Under Article 32 of the constitution, the state is strictly responsible for the protection of the right to life of its citizens. This obligation is further reinforced by Article 6 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), which recognises the inherent right to life and requires states to ensure its protection by law.

In Rylands v. Fletcher and T.C. Balakrishnan Menon v. T.R. Subramanian (1968), the courts held the defendants liable for damages caused by hazardous activities, even though the work had been delegated to contractors. Similarly, in Writ Petition No. 7650 of 2012, Z.I. Khan Panna vs. Bangladesh and Others, concerning the Jihad case, the High Court Division observed that the incident represented clear negligence by the Fire Service and Civil Defence and Bangladesh Railway, resulting in a violation of the fundamental right to life. The court further applied the maxims res ipsa loquitur (the principle that the mere occurrence of some types of accident is sufficient to imply negligence) and the principle of strict liability (Writ Petition No. 12388 of 2014, Children's Charity Bangladesh Foundation vs. Bangladesh and Others).

Examples from other jurisdictions also show that governments assume moral and legal responsibility when failures lead to loss of life. Therefore, by merely paying a nominal amount of compensation or forming an investigation committee, the state cannot absolve itself of responsibility. The government must ensure accountability through proper investigation and disciplinary action against officials of the concerned authorities.

Md Tanvir Mahtab is lecturer at the Department of Law in Bangladesh University and an advocate at the Dhaka Judge Court.

Sadia Shultana is a research associate at Law Bridge.

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments