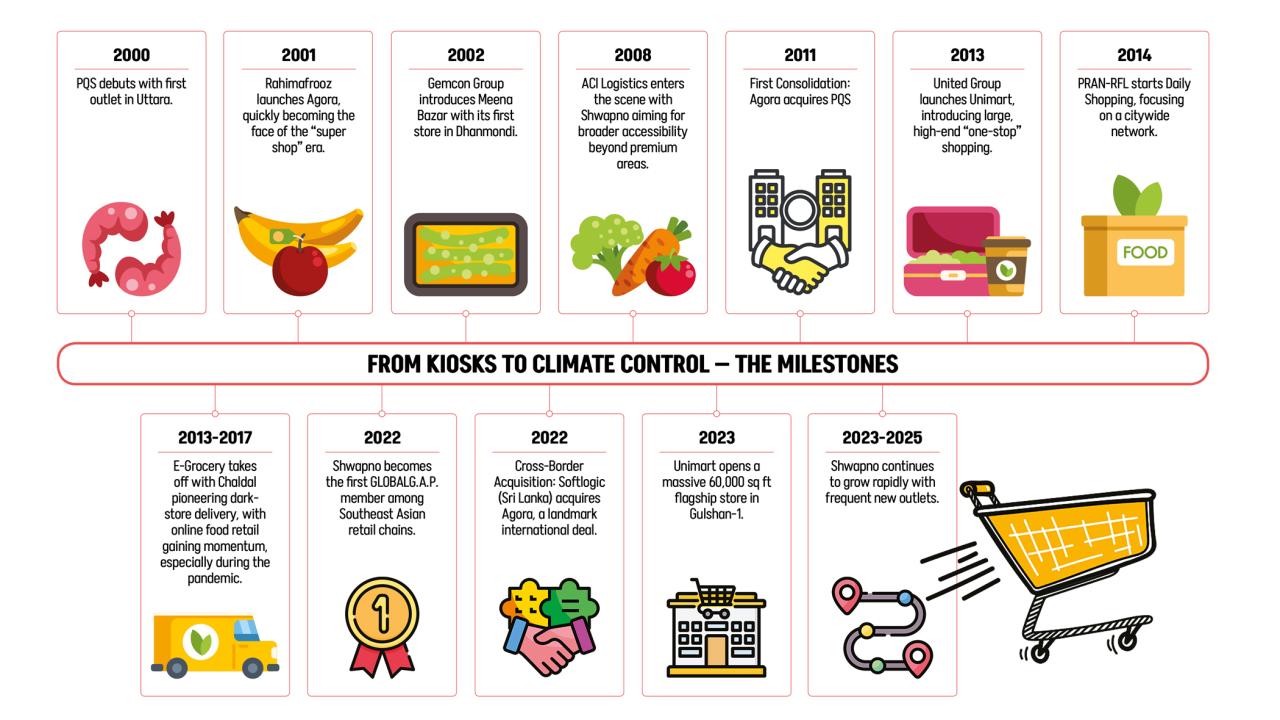

Wet markets to super shops: How Bangladesh learnt to shop smart

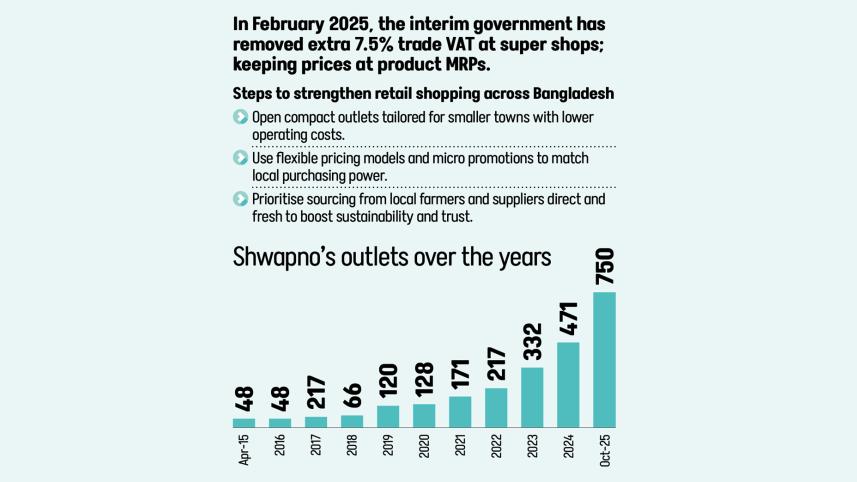

Bangladesh's retail and wholesale sector now contributes nearly 14% of GDP, with organised retail growing faster than any other segment. Super shops like Shwapno have expanded to over 750 outlets nationwide, redefining how the nation buys its daily essentials.

The smell hits first. In Dhaka's Karwan Bazar, the air is thick with the mingled scent of hilsa, coriander and sweat. Under tarpaulin roofs sellers shout prices over the hum of traffic, feet splash through puddles, and bargaining is both ritual and survival. For decades that was the unshakeable rhythm of Bangladeshi life. A world of trust built on faces, not price tags.

Now picture the contrast: the hum of an air conditioner, aisles lined with fluorescent lights, trolleys gliding over polished floors and the faint electronic beep of a barcode scanner. In less than two decades grocery shopping in Bangladesh has quietly changed, and everyday habits have slowly shifted. What was once a social act rooted in haggling and habit has become a streamlined experience defined by hygiene and efficiency. The question is not whether the shift happened but how an entire nation learnt to shop smart.

Time changed how we shop

Until the early 2000s the typical Bangladeshi household revolved around a set routine. Each week family members visited the local mudir dokan for basics and the nearest wet market for perishables. The neighbourhood grocer was more than a merchant; he was an informal banker and an extension of family life. Buying rice or lentils came with gossip, community updates and the occasional loan noted in a worn notebook. The experience was deeply personal but far from perfect. Prices fluctuated daily, and hygiene could be inconsistent. For working mothers and domestic helps alike, grocery shopping was both a duty and a drain on time. In the absence of refrigeration and standardised packaging, trust rested entirely on human relationships. It was a system that worked until modern life made it hard to sustain.

Trust becomes everyday currency

As Dhaka's skyline rose with apartment blocks and its streets filled with urban professionals, expectations shifted. With more women in the workforce and smaller family units, time became precious. Exposure to organised retail abroad sparked fresh demands for cleanliness and convenience. A growing middle class wanted fixed prices, neat aisles and clear separation between meat and vegetables. The first organised super shops appeared, but adoption was slow. Many shoppers dismissed them as costly and distrusted packaged produce until quality controls and brands proved reliable.

Chains like Shwapno and others helped by showing how branding accessibility and reliable sourcing could bridge tradition and modernity. Packaged goods with clear expiry dates and labelled origins reassured wary buyers. Investment in cold chain logistics meant fish, meat and dairy reached stores fresher and safer. Smaller vendors adapted too, some by improving hygiene or teaming with collection points and micro distribution. The change widened choice and convenience while keeping many neighbourhood sellers in the mix for fresh finds and daily chat and local traditions.

The pandemic propelled digital habits

The real breakthrough came in 2020 when the pandemic turned shopping habits inside out. Overnight crowded wet markets that once pulsed with life became sites of fear. Health-conscious consumers sought distance and reliability, and super shops stepped in. Online ordering, digital payments and doorstep delivery became lifelines. Once people learnt groceries could arrive with a few taps, the old model of navigating crowded lanes felt outdated. The pandemic did not just accelerate digital retail; it normalised it. For many, that was the moment grocery shopping permanently moved from a social ritual to a private, efficient routine.

The road ahead and memory

Today urban consumers are as likely to tap an app as to walk into a store. QR code payments, loyalty programmes and express deliveries are part of everyday life. Shopping is more about efficiency, a task to be managed, not an outing to be enjoyed. Behind the scenes retailers have built cold chain networks, warehouse automation and sourcing partnerships to keep up with demand. Organised retail, though still a fraction of total retail activity, has been growing faster than other segments, and it is expanding beyond megacities into secondary towns.

Still nostalgia refuses to fade. For many the smell of fresh coriander, the banter of vendors and the art of bargaining remain irreplaceable. The super shop may have redefined convenience, but it has also reshaped community. The wet market was a place where neighbours met and stories were exchanged; now shopping is often solitary or digital. In that exchange the country has gained cleaner food, consistent quality and more time for family, but it has also tidied away a part of its collective character.

From the clamour of open markets to the calm of climate-controlled aisles, Bangladesh's journey from wet markets to modern stores is a story of development and desire. A generation ago shopping meant trusting a person; today it often means trusting a system. That shift is one of the clearest symbols of how the country itself has modernised.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments