When the alleys knew our names

There was a time when Dhaka's narrow lanes knew us better than we knew ourselves. Long before the flyovers sliced the sky and long before every passer-by walked around wrapped in earbuds like private citizens of their own worlds, these alleys held entire universes.

They were noisy, affectionate, and annoyingly invested in every detail of your life. They were also comforting in ways we only understand now, when the warmth has thinned and the doors have learned to close.

Back then, it was impossible to cross your own lane without being interrogated by at least five neighbourhood uncles who believed they had been personally appointed as guardians of your moral development.

A simple trip to the corner shop could take half an afternoon because everyone had something to say. And they said it with conviction. Sometimes too much conviction.

On your way home from school, Uncle Ali would stop you to ask how the exams were going and then remind you to give his regards to your father. Before you made it twenty steps, an aunty leaning out from her balcony would call down and say she had not seen your mother yesterday and wanted to know if everything was alright.

Concern sounded like an accusation, but the love was genuine. The alleys ran on a kind of collective surveillance that, strangely enough, made you feel protected.

Even the neighbourhood barber felt entitled to weigh in. From his tiny tin-roofed shop, he would shout, "Your hair has grown too much. Come tomorrow, I will fix it."

The vegetable vendor would ask if your mother needed papaya or if she would like some fresh cauliflowers instead. And the corner shopkeeper would inspect you suspiciously the moment you stood too close to the cigarette shelf because to him, and to the entire lane, you were still a child.

Back then, emergencies were never faced alone. If someone fell sick, neighbours rushed in before the family could even ask, bringing food, medicines, and half the lane's advice.

Children could roam freely because every adult kept an eye out. Every afternoon, all the kids would gather in one house to play; the doors were always open, and people trusted each other in ways that feel almost unreal today.

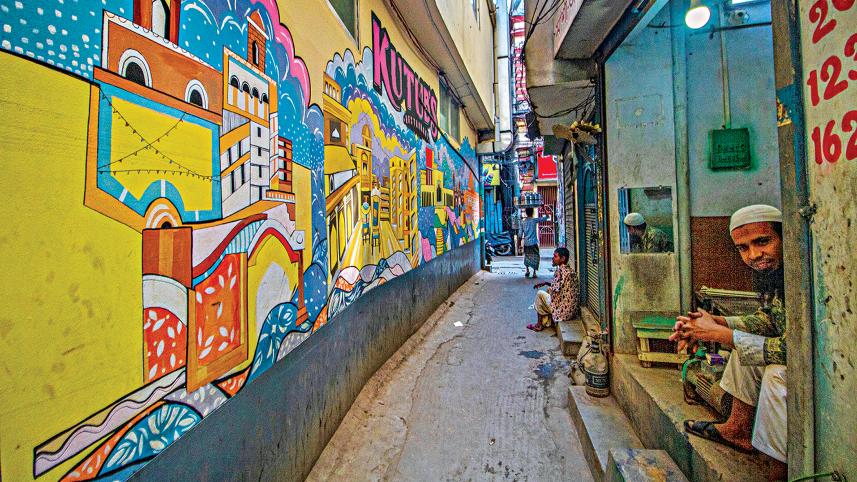

Those were the days when Dhaka still felt like a patchwork of living rooms rather than a network of private fortresses. Today the alleys are quieter. People walk faster. Eyes down, mind elsewhere. Neighbours slip past each other as if they share nothing but the same footpath.

"I do not recognise half the faces in this lane anymore," said Hasna Ahmad, who has lived in Kalabagan third lane for more than forty years. "We grew up knowing every family. If someone cooked biryani, three houses would get a share. Now doors stay shut. People barely greet each other."

She spoke of Eid mornings when children went from door to door collecting salami and blessings without hesitation, moving from one home to the next as if the whole lane belonged to them. "There were no divisions then. Every festival, every sorrow, it belonged to all of us."

Across the city in Mohammadpur, retired professor Shahana Azim of Tajmahal Road shared the same grief. "Once our alley was one big extended family," she said. "When a child had exams, aunties scolded them collectively. When someone bought a new television, half the lane came to watch the nine-o-clock drama together. Now everyone is too busy being lonely."

"People are just into themselves now," Hasna added quietly. "They don't trust anyone outside their little circle. We used to live like a community. Now everyone lives like an island."

In Dhanmondi 8, Afzal Rahman, now in his late forties, said the lanes were once the real guardians of children. "If you tried to bunk school, five uncles would drag you back. If you cried, ten aunties would rush with water. That kind of supervision felt irritating then. Looking back, I realise it made our childhood feel safe."

At Jigatala Bus Stand area, retired banker Motin Sarker described the alley as a giant breathing diary. "Neighbours checked in on each other all the time. If someone was late returning home, people waited. Today nobody notices even if you are gone for a week."

The alley still stands but the rhythm is gone, he said.

But the nostalgia does not come from imagining an old Dhaka that was perfect. It comes from remembering a Dhaka that was personal. A Dhaka where the alley watched you grow, corrected you, fed you, teased you, protected you. Sometimes annoyingly, but always sincerely.

Walk down those same lanes today and you see locked gates, tinted windows, rows of security cameras blinking like strangers. Conversations have been replaced by notifications. Festivals are quieter, greetings shorter. Children rarely know the names of the people living next door.

Meanwhile at Khandaker Goli in Siddheswari, shopkeeper Jalil Mia stood outside his small grocery shop that has survived three decades of construction dust and rising buildings. He remembers the lane when it had only one-storey and two-storey homes, when the wind passed freely between houses and neighbours spoke to one another across courtyards.

"Look at that building," he said, pointing to a tall apartment in front of his shop. "Twenty years ago, Mr Khan lived there with his family. Every evening, he would come to my shop and buy something small. Salt, biscuits, a packet of tea. It was not about money. It was the relationship. We talked about everything. His children called me Mama. They grew up in front of my eyes."

Jalil paused and looked at the building again. "After Khan bhai died, his children gave the house to the builders. Now it is all apartments. New people come; new people go. Nobody even knows my name."

But Jalil stays because the small things still matter to him. The few elderly customers who still come by and ask about his health. The rare afternoons when an old resident recognises him and stops for a chat. "Some days you feel the lane remembers," he said.

In Old Dhaka's Nazirabazar, Hasan Ali said community bonds still survive, but not untouched. "We still look out for one another, that much remains," he said. "But commercialisation has surrounded us. There are too many outlets, too many shops. The younger generation has moved to other parts of the city. They seldom visit. Festivals are not the same. They used to be community gatherings. Now they feel like individual events."

He remembered Shab-e-Barat nights when the whole neighbourhood lit up like a single house, and Eid mornings when the smell of shemai drifted from home to home. "Now the lights are there, the food is there, but the feeling is not the same. People live close but not together."

These voices echo the same truth. The city has grown taller and faster, but the alleys that once held its soul have grown quieter. The warmth has thinned and relationships have become lighter.

Yet the memory of the old lanes lingers. The way children once ran from one home to another without hesitation. The way aunties discussed everything from test marks to someone's suspicious new hairstyle. The way uncles held entire symposiums on someone's cricket scores at the corner tea stall. The way neighbours borrowed salt as if it were a shared resource owned by the entire block.

Back in Kalabagan, Hasna Ahmad looked at her lane and said, "Maybe cities grow. But when alleys lose their warmth, it feels like the city shrinks."

Through the fading hum of old neighbourhoods, one thing feels certain. The alleys have not forgotten us. It is we who stopped listening.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments