Bits of Halloween in Bangladesh’s ghostly lore

Fear, like folklore, is a product of geography. It grows out of the land, shaped by its climate, its rituals, and its silences. In our culture, it lingers in the swamps, in the rustle of banana leaves, in the long shadows beneath a banyan tree. Our ghosts are not foreign phantoms lurking in castles or crypts; they are rooted in soil, memory, and grief.

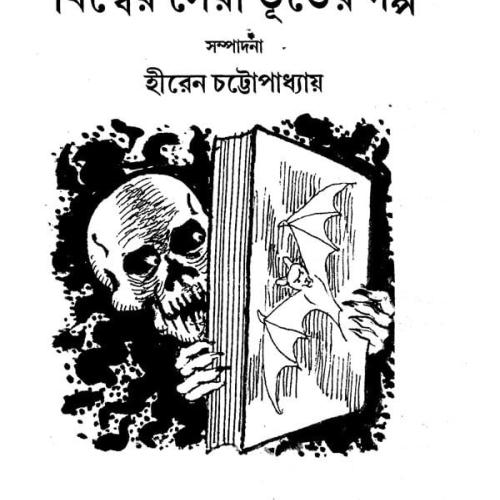

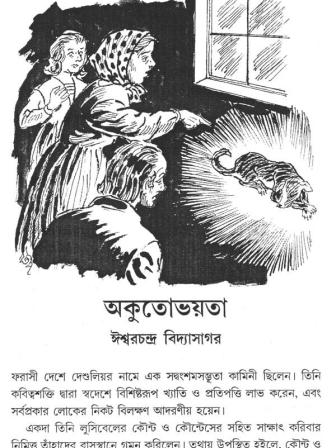

They emerge from social injustices, unfulfilled desires, and forgotten histories, and in their persistence, they remind us that the supernatural is often an allegory for the very real. Long before the Western world assigned October as the season of spirits, we had already built our own mythology of the unseen. The tradition of "Bhoot Er Golpo" (stories of ghosts and spirits) predates colonial literature, passed orally across generations. These tales were not merely designed to frighten; they were moral and psychological commentaries disguised as entertainment. They spoke of desire, injustice, and morality, using fear as the most universal language of reflection.

Among the most enduring figures of Bengali folklore is the Petni, the spirit of a woman who died unmarried or wronged in life. Described as pale and untamed, she lives near ponds or deserted groves, often preying on men who venture alone at night. Literature often depicts the Petni as a symbolic revolt against a patriarchal order that silenced women in life and myth alike.

In her spectral freedom lies an inversion of power as the woman who once lacked agency now inspires dread. Closely related to her is the Shakchunni, a ghostly figure of a married woman who dies prematurely. Identified by her conch shell bangles and vermilion, she haunts her home or other men's dreams, eternally yearning for the domestic stability denied to her. Unlike the vengeful Petni, the Shakchunni embodies longing and loss as her tragedy lies not in death but in attachment.

If the Petni and Shakchunni echo social critique, the Bhoot and Preta belong to a more metaphysical order. The term Preta, borrowed from Hindu and Buddhist cosmologies, refers to the hungry ghost, a soul trapped between worlds, cursed by its own greed or attachment. These entities, condemned to eternal craving, reflect the moral philosophies of both religions: that unchecked desire binds one to suffering.

When adapted into local folklore, the Preta evolved into the Bhoot; an amorphous, restless entity haunting fields, rivers, and trees. Its existence speaks less of horror and more of incompleteness as a spirit unable to move on because the living refuse to forget. Other apparitions, however, belong to a lighter tradition of rural imagination. The Mechho Bhoot, for instance, is a fish-loving ghost who sneaks into kitchens or ponds to steal fish. It is perhaps the most Bengali of spirits as it is hungry, mischievous, and strangely familiar.

The Daini also occupies a particularly fearsome place in Bangladeshi folklore. Unlike spirits who are restless or symbolic, she is an active agent of malevolence, often depicted as a woman practicing black magic or sorcery. Legends attribute to her the ability to curse families, destroy crops, summon illness, or manipulate weather, and she is frequently linked to jealousy, envy, or social transgression. In many villages, they are said to inhabit the peripheries of communities or isolated homesteads, emerging under the cover of night, sometimes shape-shifting into animals to carry out their deeds. Her presence in folklore functions both as a cautionary tale and as an explanation for misfortune, encapsulating communal anxieties about power, morality, and societal norms.

Then comes the Mamdo Bhoot, emerging from Muslim folklore, often portrayed as a prankster inhabiting graveyards and mosques. Neither sinister nor saintly, these figures demonstrate how the supernatural in Bengal absorbed plural influences with each leaving a linguistic and cultural imprint on the way the region imagined fear. Distinctively Bangladeshi perhaps is the world of the Jinn.

Between the Muslim majority's religious cosmology and folk belief arises the conviction that supernatural, unseen beings inhabit the same world as we do. The Jinn, are shape‑shifters, unseen but palpable, capable of possession, whispering, moving objects, altering atmosphere. Many families recount experiences of Jinns in abandoned rooms, at the edge of tea estates, or in narrow alleys after midnight. They remain culturally significant because they bridge religion, fear and the unpredictable in everyday life.

Among the most haunting of all is the Nishir Daak, a voice that calls one's name in the dead of night. Those who answer are said never to return. The story's simplicity makes it powerful. It warns against the instinct to trust the familiar, against the impulse to respond to what one cannot see. Some interpret it as a metaphor for temptation; others as a narrative explanation for disappearances in treacherous rural terrain. Then there is the Aleya, or ghost light, another legend deeply entwined with Bengal's physical landscape. Fishermen and travellers have long reported seeing bluish flames flicker over marshes and wetlands at night. Science attributes these to methane oxidation, a phenomenon caused by decomposing organic matter. But for generations, these lights have been seen as souls of the drowned, wandering restlessly or guiding the lost.

During colonial times, ghost stories began migrating from oral tradition to literature. British ethnographers dismissed them as native superstition, but writers recognised their metaphorical richness. Rabindranath Tagore's "Khudito Pashan" (The Hungry Stones) reimagined haunting as a psychological experience and an allegory of colonial memory and human desire. Bibhutibhushan Bandyopadhyay's spectral tales, often set in forests and riverbanks, portrayed ghosts not as villains but as silent participants in the natural order. Later, Satyajit Ray's "Monihara" and "Goopy Gyne Bagha Byne" adapted these motifs for cinema, fusing rural superstition with human melancholy and wit. Through such retellings, our local "Bhoot Er Golpo" evolved from oral legend to literary art.

In contemporary Bangladesh, these stories have been adapted yet again. The modern urban landscape, filled with abandoned houses, university dormitories, and unlit highways, has produced its own folklore. Stories circulate online about haunted hostels, cursed lifts, and ghostly figures on CCTV footage. These narratives continue an ancient cultural instinct: to locate mystery within the everyday. The internet has become a new kind of village courtyard where fear travels faster but remains just as communal.

What binds all these stories together is their human core. The ghosts of Bengal are rarely symbols of pure evil. They are extensions of unresolved emotion manifested into form. Each spirit, in its own way, speaks to a social truth. Thus, to speak of Bengali ghosts is not to indulge superstition but to acknowledge continuity. These stories endure because they hold the collective memory of a region where life and death often coexist within a single breath. They are not foreign horrors imported through cinema or festivals, but reflections of our own landscape, emotional and historical.

In a world increasingly enamoured with Western symbols of Halloween, our ghosts remain profoundly local. They belong to the ponds and trees, to songs sung in whispers, to the quiet after dusk. And as long as these spaces survive in memory, the "Bhoot Er Golpo" will continue to live; not as frightful tales, but as echoes of a culture that has always known how to turn fear into folklore.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments