The Bhola Cyclone and the making of Bangladesh

The 1970 Bhola cyclone was among the deadliest natural disasters in recorded history. It struck the coastal belt of what was then East Pakistan in November 1970, killing hundreds of thousands and destroying entire communities. Beyond its tragic and immediate human costs, it likely had profound political consequences. Within a year, the world witnessed the birth of a new nation.

For many who lived through it, the cyclone marked the moment when an old order lost its moral authority. It exposed how distant and indifferent the central government in West Pakistan had become to the suffering of those it governed. In that sense, Bhola did not simply destroy villages; it revealed the fragility of the bond between ruler and ruled.

Scholars of Bangladesh's political and economic history have long debated what truly brought about Bangladesh's independence. Some point to economic disparities and cultural divisions that had existed since 1947. Others emphasize the leadership of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman and the growing movement for regional autonomy. But important observers present in that historical moment like Archer Blood, US consul general for East Pakistan stationed in Dhaka in 1970 who famously sent telegrams to US President Richard Nixon and Secretary of State Henry Kissinger to draw attention to the Pakistan army's atrocities in Bangladesh, described the Bhola cyclone as the real trigger for separation. The USAID Mission Director Eric Griffel similarly called the cyclone "the real reason for the final break". But others believe that the cyclone's role has been overstated, that it merely accelerated an inevitable process. Professor Rehman Sobhan, one of the architects of the 1966 Six Point Movement, has argued that the storm only dramatized an already inevitable political outcome.

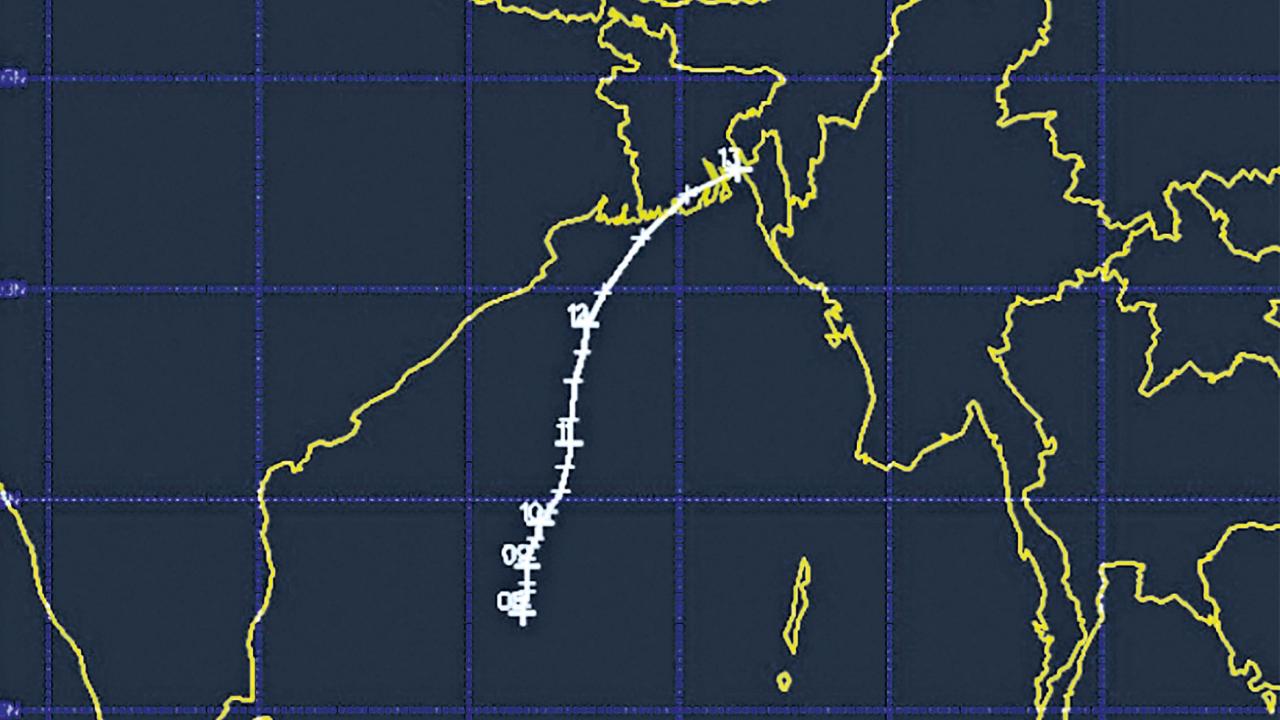

We revisit this conversation by uncovering long-forgotten satellite images of the cyclone's devastation that was archived by the U.S. National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA)'s satellite services group. The ITOS-1 satellite, funded by the U.S. Department of Defense, was among the most advanced real-time cloud monitoring systems of its time and a critical Cold War asset. The satellite was only operational from January 23 to November 16, 1970 when a tape recorder malfunction halted data transmission. The Bhola cyclone made landfall on November 12, 1970, so the satellite captured crucial imagery of cloud cover distribution and radiation. We apply modern atmospheric science research methods to these images to infer the intensity of cyclone winds felt in every thana in East Pakistan. We also digitize the voting records in every electoral constituency in 1954 and in 1970, as well as the birthplaces of every one of the 206,000 freedom fighters who bravely took up arms to engage in guerrilla warfare against the Pakistan army. We statistically connect all these data streams and apply modern empirical research standards to explore whether the Bhola cyclone indeed played any catalytic role to turn the discontent that already existed amongst Bengalis in the 1950s and 1960s into collective action at a decisive moment in history.

The Bhola cyclone gave the people of East Pakistan a common experience of abandonment. It became a moment of recognition that the government ruling from the West neither could nor would protect them.

The Storm and the Silence

When the cyclone made landfall on the night of November 12, 1970, winds of more than 200 kilometers per hour and tidal surges over ten meters high swept across the Bengal delta. The storm submerged entire islands such as Bhola, Hatia, and Manpura and carried seawater far inland. More than 350,000 people perished, and millions lost their homes and livelihoods. In any disaster, the government's first test is its response. The contrast between what people expected and what they received was striking. While the international community mobilized quickly, the Pakistan government's own relief efforts arrived late and reached few. Reports from the time describe aid shipments piling up at Lahore airport while the victims in the delta waited for food and medicine. President Yahya Khan's absence was noteworthy.

The absence of the Pakistan state was conspicuous. The USAID officer Eric Griffel later observed that "hundreds of planes came in from all over the world. For the first three days, nothing came from West Pakistan. It was noticed." Newspapers carried photographs of relief goods stranded far away from where they were needed. The episode took on deep political meaning. Many in East Pakistan already felt marginalized within a state that concentrated wealth, power, and military authority in the western wing. The cyclone and the state's callous response revealed the mindset that allowed such vast disparities to persist, and drew people's attention to those inequalities in the most striking manner.

A Political Turning Point

The timing of the disaster gave it unusual weight. Only four weeks after the cyclone, Pakistan held its first democratic national election in over fifteen years. Sheikh Mujibur Rahman's Awami League was campaigning on a platform of economic and political autonomy. In the weeks after the cyclone, Mujib suspended much of his electioneering and instead organized local relief, traveling by boat through inundated areas.

To ordinary citizens, this contrast between local compassion and official indifference mattered. When voters went to the polls in December 1970, their choice was informed not only by policy preferences but also by recent experience. Our econometric analysis of the archival data show that constituencies most affected by the cyclone and least served by relief gave significantly higher support to the Awami League. The Awami League won a sweeping victory, securing 160 of 162 seats in East Pakistan and an overall majority in the National Assembly. In principle, this result entitled Sheikh Mujibur Rahman to form the next government of Pakistan. In practice it led to confrontation, as the military regime in West Pakistan refused to transfer power.

From Election to War

The political impasse of early 1971 soon escalated into repression and eventually open conflict. The non-cooperation movement in East Pakistan became an armed resistance after the military crackdown of March 25. Digitizing archival records allowed us to trace how this transition unfolded.

The Ministry of Liberation War Affairs in Dhaka maintains a verified list of more than 200,000 freedom fighters. Mapping their birthplaces reveals a pattern: the guerrilla warriors were disproportionately drawn from the upazilas/thanas that had suffered most during the cyclone. Statistical analysis indicates that places that experienced greater storm intensity – and especially the subset of those areas where little or no government relief was provided – sent more fighters into the liberation forces. It is difficult to draw a direct line from environmental disaster to armed struggle, but the evidence suggests that shared trauma can help transform grievance into solidarity. The Bhola cyclone gave the people of East Pakistan a common experience of abandonment. It became a moment of recognition that the government ruling from the West neither could nor would protect them.

Revisiting the Historical Debate

By 1970, the imbalance between East and West Pakistan had already become undeniable. Per capita income in the East was roughly one-third lower than in the West, even though exports from the East, especially jute, provided most of Pakistan's foreign exchange. Political and cultural tensions had grown over language, representation, and resource allocation. The foundations for discontent were already in place.

Yet, history often turns on moments when slow-burning grievances meet sudden revelation. The Bhola cyclone was such a moment. It converted frustration into certainty and made separation seem not just desirable but necessary. The main headline in the Daily Ittefaq on January 18, 1971 captured the mood: "Awami League's huge victory even in cyclone-hit areas. Victory for autonomy on the devastated coast of Bengal."

Why Bangladesh Succeeded

Bangladesh's independence story also speaks to a broader question: why do some movements for autonomy succeed while others fail? Many separatist struggles, from Biafra to Tamil Eelam, ended in defeat. The difference often lies in the ability of a movement to build mass unity, moral legitimacy, and for citizens to risk their lives to take up arms against a militarized government.

The Bhola cyclone provided such conditions. It united the population across social and economic divides, and it gave the call for independence a moral foundation. The cause was no longer just political autonomy but also human dignity. When citizens saw that their lives were expendable to the state, the demand for self-rule gained a force that military repression could not extinguish.

Lessons Beyond 1971

The Bhola experience has relevance far beyond Bangladesh. Around the world, natural disasters have often acted as moments that expose how states treat their citizens. The inadequate response to the 1978 earthquake in Iran eroded confidence in the Shah's regime. The 1976 earthquake in Tangshan, China, contributed to shifts in political leadership and policy direction.

These examples point to a larger truth. Natural disasters are tests of governance. They measure a government's capacity and its moral commitment to its people. When the state fails that test, the consequences reach far beyond the immediate tragedy.

Bangladesh itself internalized this lesson. In the decades since independence, it has built one of the most effective community-based cyclone preparedness systems in the world. Warning systems, shelters, and local volunteer networks have dramatically reduced mortality from major storms. The country's capacity to respond to disasters is now studied as a model in international development. That transformation reflects both institutional learning and collective memory.

The Human Dimension

Behind every statistic about Bhola were individual lives. Diaries and oral histories from survivors describe both loss and awakening. A farmer from Barisal later recalled, "We had always known that our wealth went west. But when the storm came and no one helped us, that is when we understood we were on our own."

Such realizations are rarely captured in political theory, yet they form the emotional core of state formation. Revolutions and independence movements succeed not only through ideology or organization but also through shared moral conviction. After Bhola, that conviction spread rapidly.

Reflection and Responsibility

More than fifty years later, Bangladesh has transformed itself from a war-torn country into one of the fastest-growing economies in South Asia. Yet the questions raised by its birth remain relevant. What makes a state legitimate? What binds citizens to their government in times of crisis?

The Bhola cyclone offers a reminder that legitimacy is not inherited but earned through empathy and action. When the state fails to act, people begin to imagine a different one. In 1971, that imagination became reality. This is not only a story of Bangladesh's past but also a caution for the future. As climate change increases the frequency of extreme weather events, governments around the world will face similar tests. How they respond will determine not only lives lost or saved but also the trust that sustains political communities. Bangladesh's journey from devastation to development shows that lessons can be learned and institutions strengthened. But it also teaches that moments of neglect are never forgotten. The Bhola cyclone revealed what kind of state Pakistan had become, and in doing so, it helped its people imagine what kind of state they wanted to build instead.

Sultan Mehmood is an Assistant Professor of Economics (tenure-track) at the New Economic School in Moscow. the author can be reached at smehmood@nes.ru

Ahmed Mushfiq Mobarak is the Jerome Kasoff '54 Professor of Management and Economics at Yale University. The author can be reached at ahmed.mobarak@yale.edu

To read the full study, please click here: https://tinyurl.com/1970cyclone

Send your articles for Slow Reads to slowreads@thedailystar.net. Check out our submission guidelines for details.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments