On mothers, monsters and myths: A look at the Mary before the Mary

In a wilting summer swelter of 1797 in London, a name was born twice–mother Mary Wollstonecraft wound the clock of daughter Mary Wollstonecraft (Godwin)'s life, for the very first time.

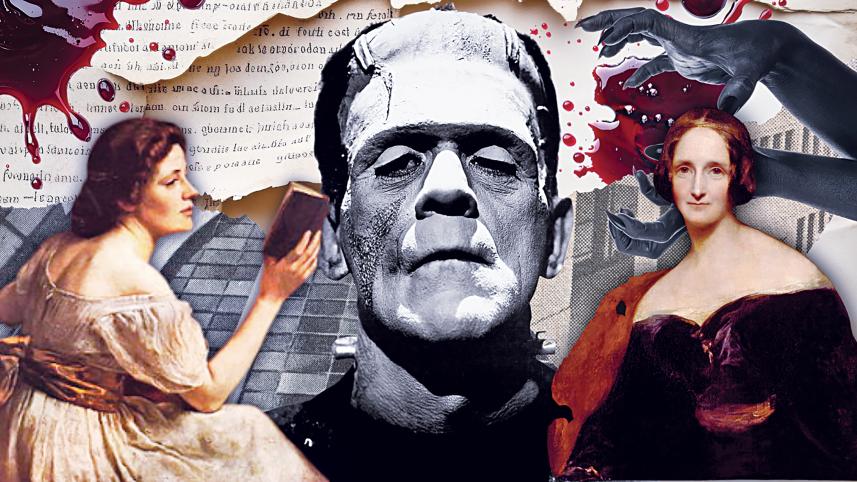

At that moment, both Marys stood at the brink of their lives—one with a foot in the grave, the other crawling toward a future of myth, invention, and literary resurrection. The daughter writhing into the world would soon go on to become the Mary we all know and love, the Mary Shelley who authored the undying monster of Frankenstein (1818).

Unfortunately, Wollstonecraft does not survive to influence the little girl alive, but undoubtedly slithers her way through to her as a haunting ghost of social and literary legacy, which nurtures Mary Godwin into her creative flowering. Although seldom a topic at the table, the mother behind the monster is pivotal to igniting the flare in the teenage genius, setting the ravishing responses against hypocritical politics, the Gothic ardour with which she lived, and the unconventionality that became Shelley's blueprint.

For the sake of clarity, the essay will be viewing the mother as Wollstonecraft, through the lens of the daughter, Shelley, to fully dissect the often overlooked pillars she left behind as parent, philosopher, and the proto mother of feminism.

Wollstonecraft's bequest bears several pieces of work strewn throughout her life revolving around society, its schemes, and the inequality that governed the crises of the time. As an early supporter of the French Revolution, her earliest critically acclaimed work was a clapback at British statesman and political theorist Edmund Burke, who wrote a political pamphlet defending the monarchy and empathising Antoinette in what Mary characterises as "unnecessarily gendered language" that only achieves a sexist undertone and supports "tradition for the sake of tradition." In her curt feminist rebuttal titled A Vindication of the Rights of Men (1790), Wollstonecraft criticises the bias for passivity in women, the theatrical tableau that is reserved for only the "sublime and beautiful" queen and not the starving housewives driven to the streets because they lacked the means to feed their families.

Unfortunately though, despite its pinch-hitting take that caused it to sell out in just three weeks, the year of 1790 was not particularly attributed to the acceptance of female writers, and the piece was soon thrown down. It was only until the late 20th century when sustained critical study was carried out by feminist scholars like Claudia Johnson who praised it to be "unsurpassed in its argumentative force".

However, the preeminence of her moral compass is illustrated best in her most incandescent work, the 1792 essay "A Vindication of the Rights of Woman", in which Wollstonecraft abandons the ornamental niceties expected of female writers and instead performs a kind of ideological vivisection on the culture that manufactures feminine weakness. Far from depicting women as innately fragile, she insists they are made so "rendered weak and wretched" by an education designed to stunt them into "spaniel-like affection" rather than moral independence. This argument is not merely moral but anatomical: she dissects how society engineers its own monsters by denying women the rational training that forms virtue, which is a mesial structure, creating what she calls "artificial, weak characters"—creatures built for pleasing rather than thinking.

She went on to demolish Rousseau's 'Sophy', making the critique especially telling. Rousseau's ideal woman was a deliberately dependent, docile creature trained to exist only for men's comfort and to reflect male virtue rather than possess any of her own. Wollstonecraft called his pedagogical fantasies "absurd sophisms," exposing how his notions were nothing more than a carefully curated dependency for the loophole for means of control over them. Reading it now, the text feels like an early autopsy of social monstrosity, an almost Gothic recognition that grotesques are not born but assembled, piece by piece, by the environments that betray them.

This very conceptual phantom almost glides into her (Wollstonecraft's) daughter's imagination. Shelley's creature, abandoned and misshapen, isolated from community, is not far from the ideology, turning it into the living (or undead) proof of Wollstonecraft's thesis that society, not nature, is the true manufacturer of monsters.

The work provides a faint galvanising pulse that Shelley would later amplify in ways uniquely her own.

Mary grew up in Godwin's radical household, a place where she received an unlikely education for a girl of her time. This home, curtained by the absence of the mother Godwin openly revered as the most extraordinary woman of the age, led Mary to learn of her mother first as myth, then as a political and emotional inheritance. Even her relationships echoed that lineage, notably her relationship with Gilbert Imlay with whom she had Fanny Imlay, Mary's half-sister.

Her carefree romances, and sentiments published in the Letters Written in Sweden, Norway and Denmark (1796) must have deeply shaped the emotional codes in Shelley. Wollstonecraft's turbulent past; the charged, unconventional environment that taught Mary to feel, see and think, is displayed animatedly in her relationship with the married Percy Shelley, who she, ironically, is rumoured to have met at her mother's grave. In an elaborate way, her mother's grave played Cupid, tying her strings to the person whose early encouragement and editorial involvement in Frankenstein ushered her towards an unleashed potential.

Shelley's imaginative framework, then, emerges as both an extension and a divergence from Wollstonecraft's legacy. Growing up without her mother's presence nurtured no stabilising maternal reference, a condition that shaped Mary's earliest understanding of selfhood and emotional precariousness. This absence forms a clear parallel to the Creature's first consciousness in Frankenstein—a being confronted with existence but denied guidance, left to interpret the world without protection or instruction. Where Wollstonecraft had identified the social mechanisms that create the cultivation of weakness for the sake of compliance, Shelley internalises that insight and transforms its scale. Her mother's moral horror, rooted in systems that deform individuals through inequality, allowed Shelley to illuminate an acute view concerned with what happens when the one who holds power simply withdraws and care is withheld at the very moment it is most needed.

While Wollstonecraft believed that rational improvement could correct injustice, Shelley's narrative offers a more austere verdict, that the damage produced by abandonment can become irreversible. It is here, in this difference between reformist optimism and lived disillusionment, that Mary Shelley's own experiences most clearly refract her mother's theories into a darker, more unforgiving moral landscape.

Predominantly, Wollstonecraft's legacy moved through the world in spite of attempts to bury it. After Godwin's memoir exposed the full, unvarnished contours of her life with all aspects of her loves, failures, and defiance, she was met with a near-instant revilement that pushed her name into a cultural hush. Yet, even in that imposed silence, her ideas persisted.

Jane Austen's sly rebellions and observations of society, Eliot's ethical gravity, Woolf's reclamation of Wollstonecraft as "alive and active"—all attest to the force of a mind that refused conventionality. And while posterity has been quick to credit Godwin or the influential men around Mary Shelley for shaping a literary prodigy, the deeper inheritance lies elsewhere, specifically in the mother whose writings Mary devoured before she ever wrote a word of her own.

Strip away the scandals, the miscrediting, and the original current that set the course for Mary Shelley's success is unmistakable—it is in the womb of Wollstonecraft—the legacy before the legend, the mother in the margins, the forgotten Mary before the one celebrated.

Mrinmoyi is a cat enthusiast who likes her pottery by feminist icons and her poetry in fickle feathers. To learn an absurd amount of gossip on Godwin's group, contact her @uzma131989@gmail.com.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments